SURVIVAL AND EXILE

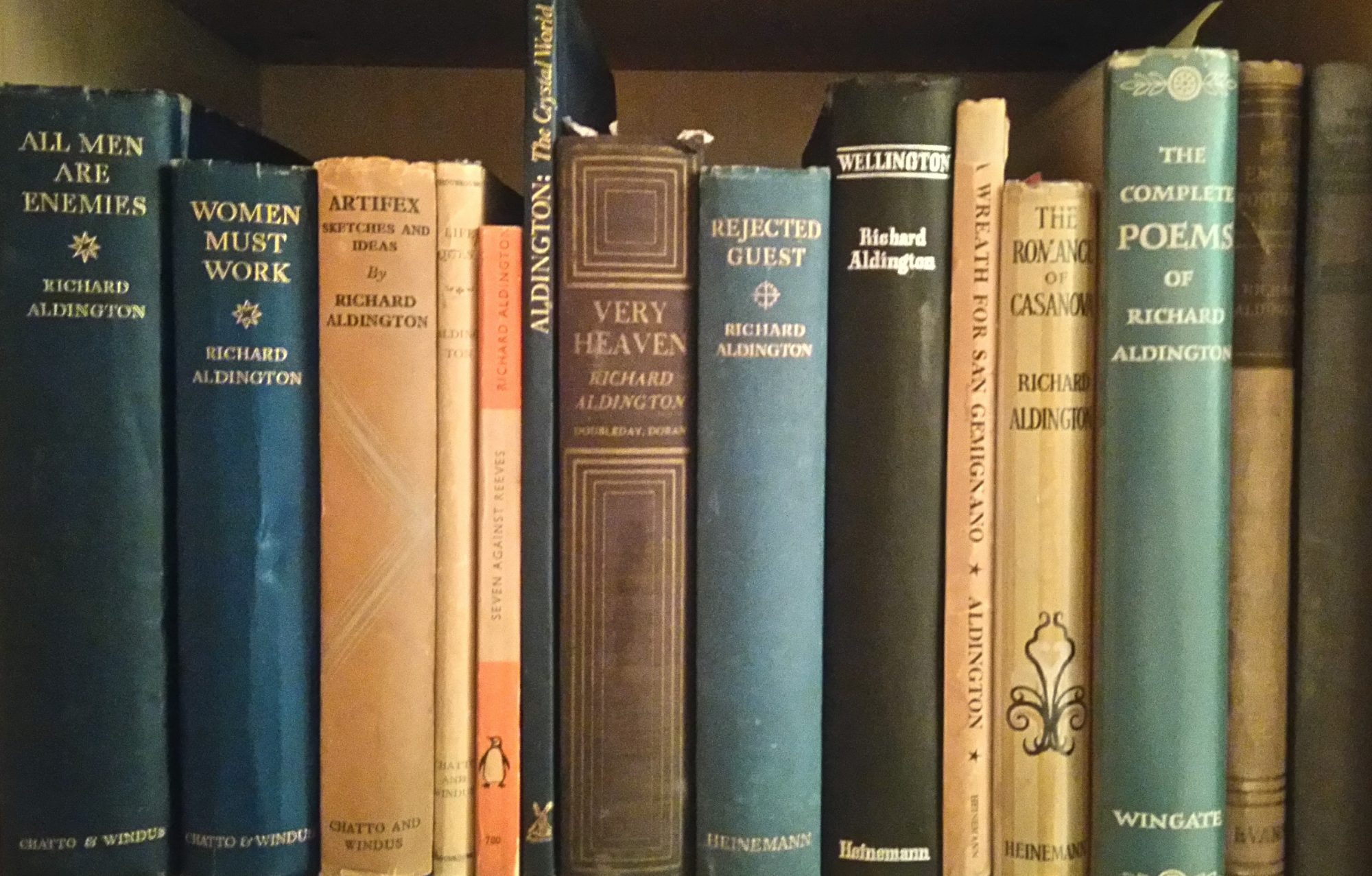

Richard Aldington’s response to his war

Saturday 2 December 2023

Richard Aldington’s Exile and Other Poems was published on 29 November 1923. This one-day conference celebrates its centenary, along with the publication of a new edition by the Renard Press, edited and annotated by Aldington scholars Elizabeth Vandiver and Vivien Whelpton.

Aldington (1892-1962) was one of the original Imagist poets, and the only Imagist who became a combatant. His name heads the list of the sixteen poets of the First World War commemorated in the Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey. He was one of only three of those sixteen who survived the war, had extensive combat experience, and suffered serious shell-shock, which would have profound long-term physical, mental and social effects.

The venue is Northeastern University London, Devon House, 58 St Katharine’s Way, London E1W 1LP. It is fully accessible.

The registration fee is £75 and covers the cost of venue hire, tea and coffee, lunch, and a copy of Exile and Other Poems.

It will be possible to attend and present remotely; there will be a charge of £10 for online attendance (a copy of the book can be added to this for a further cost which covers volume, post and packing).

Those attendees wishing to book an overnight stay on the 1 or 2 December (or both nights) can access a discounted rate at the Tower Hotel (St Katharine’s Way, London E1W 1LD) here: The Tower Hotel

To register for the conference, click here: Survival to Exile registration

Conference programme

10.00 Registration and coffee

10.30 Welcome and introduction: Dr. Catherine Brown and Professor Elizabeth Vandiver

10.40 First panel: Narrative and Time

Introduction: Dr Andrew Frayn

10.45 Dr Lizzie Hibbert: ‘Deep Time in Death of a Hero’

Philip Chester: ‘Richard Aldington’s ‘Compensation’: Paradigmatic Event and Symbolic Extrication’

Michael Copp: ‘Paris, Parallax and the Parthenon: Aldington and the Modernist Long Poem’

Professor Max Saunders: ‘“My own murdered self”: Aldington’s Anger’

12.45 Lunch and launch of the new edition of Exile, published by Renard Press

1.45 Second panel: Bodies and Minds

Introduction: Dr Kate Kennedy

1.50 Rory Hutchings: ‘”Wobbling carrion roped upon a cart…”: anti-commemoration and the corpse in Richard Aldington’s poetry’

Professor Daniel Kempton: ‘Richard Aldington’s “Bones”’

Dr Olga Shvailikova: ‘Aspects of war neurosis in Richard Aldington’s Death of a Hero and Pat Barker’s Regeneration’

3.20 Coffee

3.35 Third panel: Richard Aldington and His Contemporaries

Introduction: Dr Jane Potter

3.40 Dr Caroline Zilboorg: ‘Bridging the War: Dramatic Fools in the Work of Richard Aldington and Gregory Zilboorg’

Dr Susan Reid: ‘Murdered selves: Richard Aldington and Rachel Annand Taylor in 1923’

Professor Lee Jenkins: ‘Richard Aldington, An Englishman and Thomas McGreevy, An Irishman: Great War Imagists’

5.10 Closing remarks

Speaker biographies

Philip Chester is a retired high school teacher and Aldington enthusiast living in Deep River, Ontario. Last July, he gave a paper at the International D.H. Lawrence Conference in Taos, New Mexico as an independent scholar on Lawrence’s poem ‘Whales Weep Not’.

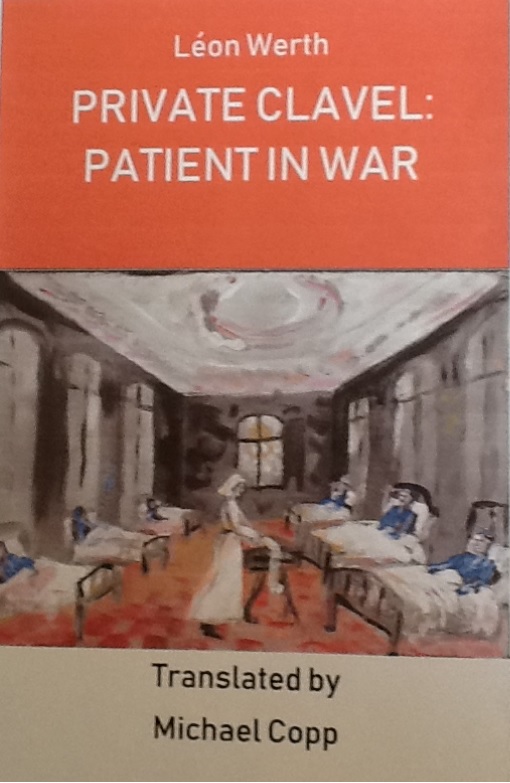

Michael Copp has an MSt in Modernist Studies. He has presented conference papers on Aldington, Imagism, Pound, Sassoon, and F S Flint. Among his books are: An Imagist at War: The Complete War Poems of Richard Aldington; The Fourth Imagist: Selected Poems of F. S. Flint; Imagist Dialogues: Letters between Aldington, Flint and Others. He has translated the war poems of Apollinaire and Cocteau and the war novels of Léon Werth.

Dr Lizzie Hibbert recently completed a PhD on the idea of deep time in English fiction published in the aftermath of the First World War at King’s College London. She has published a two-part history of the critical reception of Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End in Last Post: A Literary Journal from the Ford Madox Ford Society , an article on war and extractivism in The Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies, and a biographical portrait of Richard Aldington.

Rory Hutchings is a PhD student in the school of English at the University of Kent. His main research interests are animal studies and modernism. He is a member of the Kent Animal Humanities Network and edits the University of Kent’s peer-reviewed postgraduate journal Litterae Mentis.

Professor Lee Jenkins is Professor of English at University College Cork. She is the co-editor of three Cambridge University Press collections, Locations of Literary Modernism, The Cambridge Companion to Modernist Poetry and A History of Modernist Poetry. Her monograph, The American Lawrence, was published in 2015. She is currently completing a book for Bloomsbury’s ‘Historicising Modernism’ series on Lawrence, H.D. and Richard Aldington.

Professor Daniel Kempton taught for many years in the English Department of SUNY New Paltz. He co-directed seven biennial conferences devoted to Aldington and his circle (2002-2014) and coedited four volumes of proceedings. He has delivered conference papers on various aspects of Aldington’s work and edited several of his unpublished essays as well as his Russian journal.

Dr Susan Reid is the editor of the Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies. She is the author of D. H. Lawrence, Music and Modernism and co-editor of the Edinburgh Companion to D. H. Lawrence and the Arts, the essay collection Katherine Mansfield and Literary Modernism and the journal of Katherine Mansfield Studies (2010-12). She is currently writing a novel about Rachel Annand Taylor.

Professor Max Saunders is Interdisciplinary Professor of Modern Literature and Culture at the University of Birmingham. He is the author of Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life; Self Impression: Life-Writing, Autobiografiction, and the Forms of Modern Literature); Imagined Futures: Writing, Science, and Modernity in the To-Day and To-Morrow Book Series, 1923-31; and Ford Madox Ford: Critical Lives.

Dr Olga Shvailikova is a Senior Lecturer at Francisk Skorina Gomel State University, Belarus. She has published on Pat Barker, Sebastian Faulks, the Great War, trauma studies and contemporary British writers. Her academic interests include fiction interpretation, the British contemporary novel, modernism and postmodernism.

Dr Caroline Zilboorg is a life member of Clare Hall, Cambridge University, and a scholar of the British Psychoanalytic Council. Her books include Richard Aldington and H.D.: Their Lives in Letters, The Masks of Mary Renault: A Literary Biography, a biography of the psychoanalyst Gregory Zilboorg and the novel Transgressions. She lives in Brittany.

Organiser and chair biographies

Dr. Catherine Brown is Associate Professor of English and Director of the Graduate Research School at Northeastern University London. Her research is mainly in the fields of modernism, D. H. Lawrence, Anglo-Russian relations and vegan literary studies. She is a Vice-President of the Lawrence Society, and in 2020 co-edited with Susan Reid The Edinburgh Companion to D.H. Lawrence and the Arts. She recently wrote the chapter on ‘Modernism’ in The Edinburgh Companion to Vegan Literary Studies, 2022, and is writing a chapter on ‘D.H. Lawrence: Proto-Vegan’ for the forthcoming The Edinburgh Companion to D. H. Lawrence and the Anthropocene.

Dr Andrew Frayn is Lecturer in Twentieth-Century Literature and Culture at Edinburgh Napier University and Past Chair of the British Association for Modernist Studies. He is author of Writing Disenchantment: British First World War Prose, 1914-30 and has written a number of chapters and articles on related authors including Richard Aldington, Ford Madox Ford, and C. E. Montague.

Dr Kate Kennedy is a Supernumerary Research Fellow of Wolfson College, and Co-Director of the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing. She publishes and broadcasts widely on music and literature of the First World War, including as editor of The Silent Morning: Culture, Memory and the Armistice 1918, and author of Dweller in Shadows- A Life of Ivor Gurney (2021).

Dr Jane Potter is Reader in Publishing at Oxford Brookes University. She works on early twentieth-century writing by women, popular fiction, publishing history, and First World War writings. Her books include Boys in Khaki, Girls in Print: Women’s Literary Responses to the Great War 1914; Working in a World of Hurt: Trauma and Resilience in the Narratives of Medical Personnel in Warzones (with Carol Acton, 2015); Handbook of British Literature and Culture of the First World War (ed. with R. Schneider, 2021). Her new edition of the selected letters of Wilfred Own is to be published shortly.

Professor Elizabeth Vandiver was, until her retirement, Clement Biddle Penrose Professor of Latin and Classics at Whitman College. She is the author of Stand in the Trench, Achilles: Classical Receptions in British Poetry of the Great War. She has published numerous articles on classical reception in early 20th-century English poetry. She is currently completing a book on classical receptions in Richard Aldington’s works from the 1910s, 20s, and 30s.

You must be logged in to post a comment.