Jennifer Aldington Emous

30 January 1933 – 27 November 2019

By Vivien Whelpton

Jennifer was Aldington’s niece – the daughter of Aldington’s younger brother Tony and his first wife, Moira Osborne. She and her brother Tim, born in 1936, were brought up by their mother and grandmother after their parents separated in 1941.

Jennifer’s childhood and subsequent development were deeply affected by the Second World War: in S.E. Kent schools were closed for the duration and she and her brother were taught at home by a retired schoolteacher. Fortunately, Jennifer’s love of literature – especially Shakespeare and the nineteenth century novelists – was encouraged. She was twelve years old when the war ended and her over-protective grandmother decided that she could continue to study at home. She had many talents, apart from being an avid reader, including for drawing and painting – she did attend art school for a short while – and also for singing and for writing, but was never given the opportunity to exploit these. She loved riding and had her own horse for a while until it became too expensive to keep it; but her love of animals did lead her into breeding Yorkshire terriers and poodles. Much of her life as a young adult was taken up with caring for her grandmother and her mother. She married in 1966 and her daughter, Francesca, was born three years later. Subsequently Jennifer had an important role in helping Francesca to combine a career with bringing up her own two daughters, Saskia and Anushka, now in their early twenties.

As Tony Aldington acted as his brother’s solicitor and legal adviser, Aldington was in regular touch with him and his second family after moving back to France in 1946, but Jennifer started to write to her uncle in September 1954. His initial response was, rather unsurprisingly: ‘I have always thought that relatives and so on were people better to let alone; your letter changed my ideas on the subject.’ He told her: ‘I am an old codger now, and not very amusing, except when I get cross and slang people in print.’ (This was, of course only a few months before the publication of ‘Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Inquiry’.) However, she was not put off and they continued to correspond. In September 1961 Moira, Jennifer and Tim (newly returned from three years’ service as an agricultural field officer in Tanganyika) visited Aldington at Sury, an enjoyable time for them all, during which he took them to see the abbey at Vézelay and out for a restaurant meal; but their visit was curtailed after a week because he and Catha had been summoned to Zurich by Bryher to see the dying H.D.

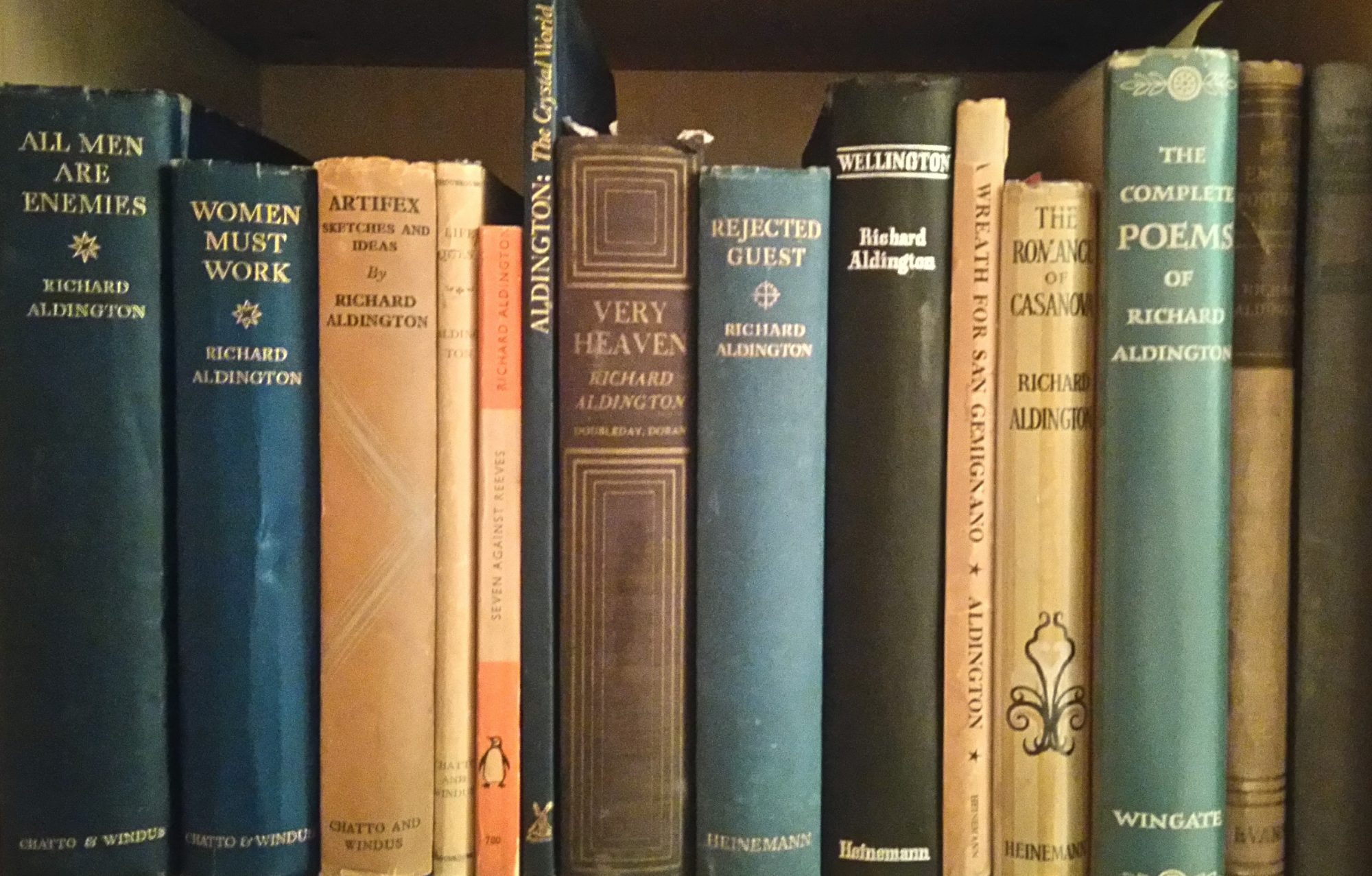

Jennifer remained an admirer of Aldington for the rest of her life and was a member of the NCLS. I was fortunate to be introduced to her in 2011 by her cousin Jane Conway, author of ‘Mary Borden: A Woman of Two Wars’. On my visits to see her in Deal in Kent, sometimes with Jane, sometimes with my husband, she shared her letters from Aldington with me and spoke of him with great affection, remarking on his generosity and good humour. Despite being crippled with arthritis, suffering from increasingly poor eyesight (a particularly tragic blow as it prevented her from reading) and in constant pain, she was welcoming and full of spirit, and her memories of her remarkable family were always entertaining. Her tales of May Aldington were fascinating and helped me understand Aldington’s fraught relationship with his mother, while her memories of his sisters, her aunts Marjorie and Patty, were poignant ones.

Until the distance became too much for her, we would meet at ‘The Black Douglas’, Jennifer’s favourite café on the seafront at Deal, where she was well known and loved. I last saw her at the end of August last year, when she and Jane and I went down to the beach to a café where Anushka worked. Knowing that I was vegan, Jennifer had thoughtfully purchased a vegan pasty for me the day before and brought it with her in the basket of her mobility scooter.

In early October, Jennifer was suffering from heart problems and contracted pneumonia. She was taken into hospital and, although discharged temporarily after a few weeks, she was soon taken ill again and returned to hospital where she died on 27 November. The Church of St Thomas of Canterbury in Deal was full of friends and family for her requiem mass on 20 December.

Jennifer is survived by her brother, her daughter and her two granddaughters. Much of the information I have about her early life was kindly given to me by Tim Aldington.

You must be logged in to post a comment.